WWF has mapped many of these pathways, which it refers to as Arctic “blue corridors,” and shared them with the IMO to help guide ship operators. Existing IMO guidelines already call on mariners to take special care around sensitive habitats, including migration routes, but conservation groups say more awareness is needed of where and when whales are likely to be present so companies and captains can plan accordingly.

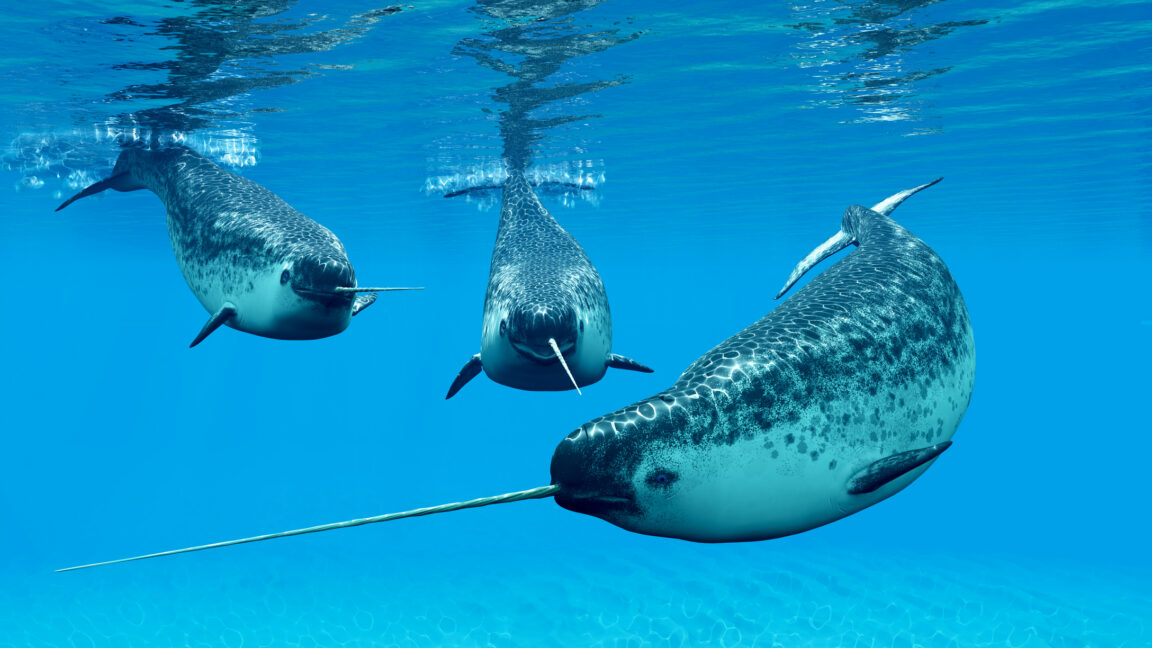

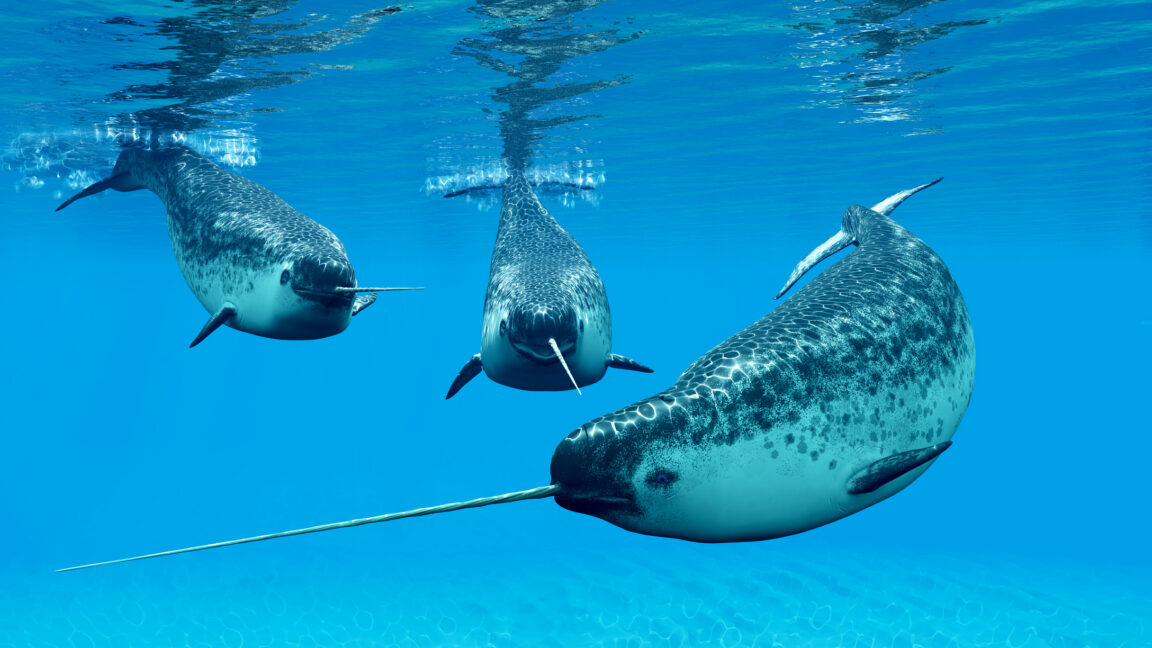

When narwhals go silent

If concrete measures are not adopted to limit the impacts of vessel traffic, underwater noise will continue to hurt whales, as well as other marine life, including fish and crustaceans, Lancaster said. Indigenous communities that rely on these marine ecosystems for food security may also be harmed.

Inuit communities in Canada and Greenland, for example, have hunted narwhals for generations to help sustain families through long winters and withstand a high cost of living in the region, according to Alex Ootoowak, an Inuk hunter who recently helped conduct a multi-year study of narwhals’ responses to shipping traffic in Eclipse Sound. That is a critically important summer calving ground for a distinct population of narwhal in Nunavut, Canada.

The study, led by researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego and Canadian marine conservation nonprofit Oceans North, found narwhals went silent when ships were passing.

“These animals are hearing and responding to ships from distances much further than we would have predicted,” said Joshua Jones, one of the study’s authors. “We learned that narwhals go quiet or move away when a ship is within about 20 kilometers of the site.” They also stopped eating.

“They stopped doing their deep dives to the bottom to feed during a ship transit,” said Ootoowak.

In Eclipse Sound, much of the vessel traffic is driven by industrial shipping linked to the Mary River Mine, a large iron ore operation on Baffin Island operated by Baffinland Iron Mines Corp., Ootoowak said. The number of tourism vessels, such as cruise ships, private yachts, sailboats, and speed boats that visit the area is also rising.

“We’re getting about 30 cruise ships a year now,” Ootoowak said. “Our waters are a lot louder than they traditionally were.”

With so much traffic and noise, Ootoowak said he worries narwhals may be abandoning their traditional calving grounds for quieter waters. Neighboring communities in Greenland are already reporting what they describe as “foreign narwhals” appearing in their waters—animals, Ootoowak said, that match the behavior and appearance of those from Eclipse Sound.

Teresa Tomassoni is an environmental journalist covering the intersections between oceans, climate change, coastal communities, and wildlife for Inside Climate News. Her previous work has appeared in The Washington Post, NPR, NBC Latino, and the Smithsonian American Indian Magazine. Teresa holds a master’s degree in journalism from the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. She is also a recipient of the Stone & Holt Weeks Social Justice Reporting Fellowship. She has taught journalism for Long Island University and the School of the New York Times. She is an avid scuba diver and spends much of her free time underwater.

This story originally appeared on Inside Climate News.

Source link