“Imagine a snowplow driving along a highway, and lifting up the plow. It leaves a clump of snow behind,” he adds. “That same sort of idea is what left the clump of cold classicals behind. That is the kernel.”

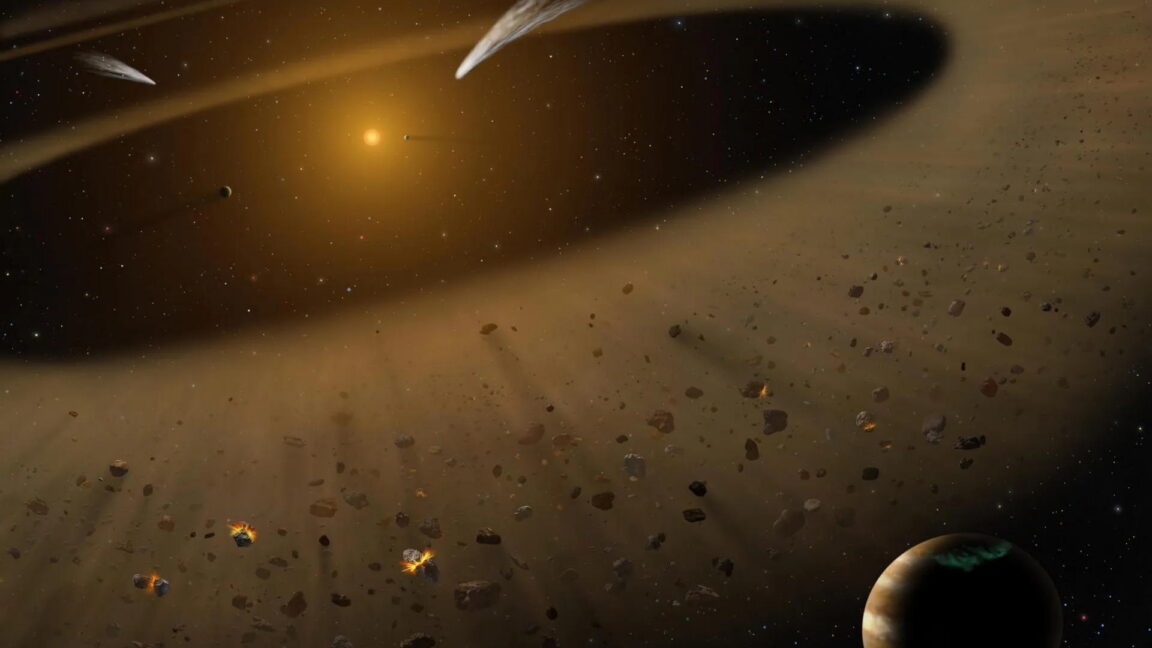

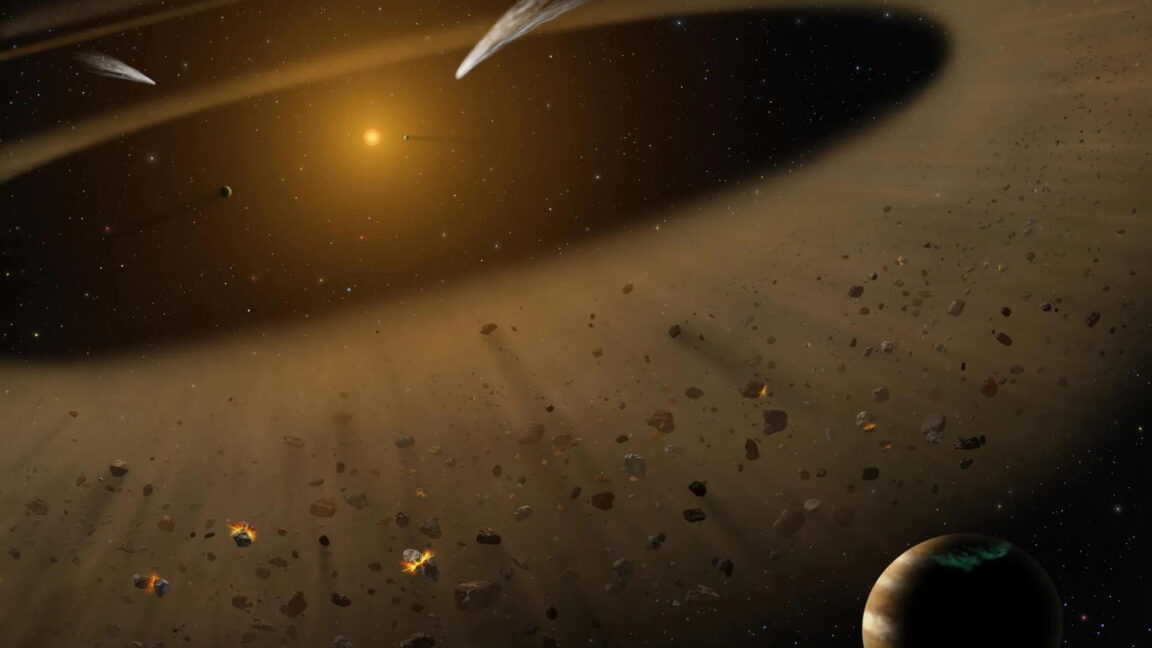

In other words, Neptune tugged these objects along with it as it migrated outward, but then broke its gravitational hold over them when it “jumped,” leaving them to settle into the Kuiper Belt in the distinctive Neptune-sculpted kernel pattern that remains intact to this day.

Last year, Siraj and his advisers at Princeton set out to look for other hidden structures in the Kuiper Belt with a new algorithm that analyzed 1,650 KBOs—about 10 times as many objects as the 2011 study, led by Jean-Robert Petit, that first identified the kernel.

The results consistently confirmed the presence of the original kernel, while also revealing a possibly new “inner kernel” located at about 43 AU, though more research is needed to confirm this finding, according to the team’s 2025 study.

“You have these two clumps, basically, at 43 and 44 AU,” Siraj explains. “It’s unclear whether they’re part of the same structure,” but “either way, it’s another clue about, perhaps, Neptune’s migration, or some other process that formed these clumps.”

As Rubin and other telescopes discover thousands more KBOs in the coming years, the nature and possible origin of these mysterious structures in the belt may become clearer, potentially opening new windows into the tumultuous origins of our solar system.

In addition to reconstructing the early lives of the known planets, astronomers who study the Kuiper Belt are racing to spot unknown planets. The most famous example is the hypothetical giant world known as Planet Nine or Planet X, first proposed in 2016. Some scientists have suggested that the gravitational influence of this planet, if it exists, might explain strangely clustered orbits within the Kuiper Belt, though this speculative world would be located well beyond the belt, at several hundred AU.

Source link