A spongy nanostructure

Northwestern University

Scanning a Qing dynasty screen with X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy

Northwestern University

courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago

China Cap, Qing dynasty (1644–1912), 18th–19th century, Gold wire, kingfisher feathers, amber, coral, jadeite, ivory, glass and silk

courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago

Scanning a Qing dynasty screen with X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy

Northwestern University

China Cap, Qing dynasty (1644–1912), 18th–19th century, Gold wire, kingfisher feathers, amber, coral, jadeite, ivory, glass and silk

courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago

Maria Kokkori/Northwestern University

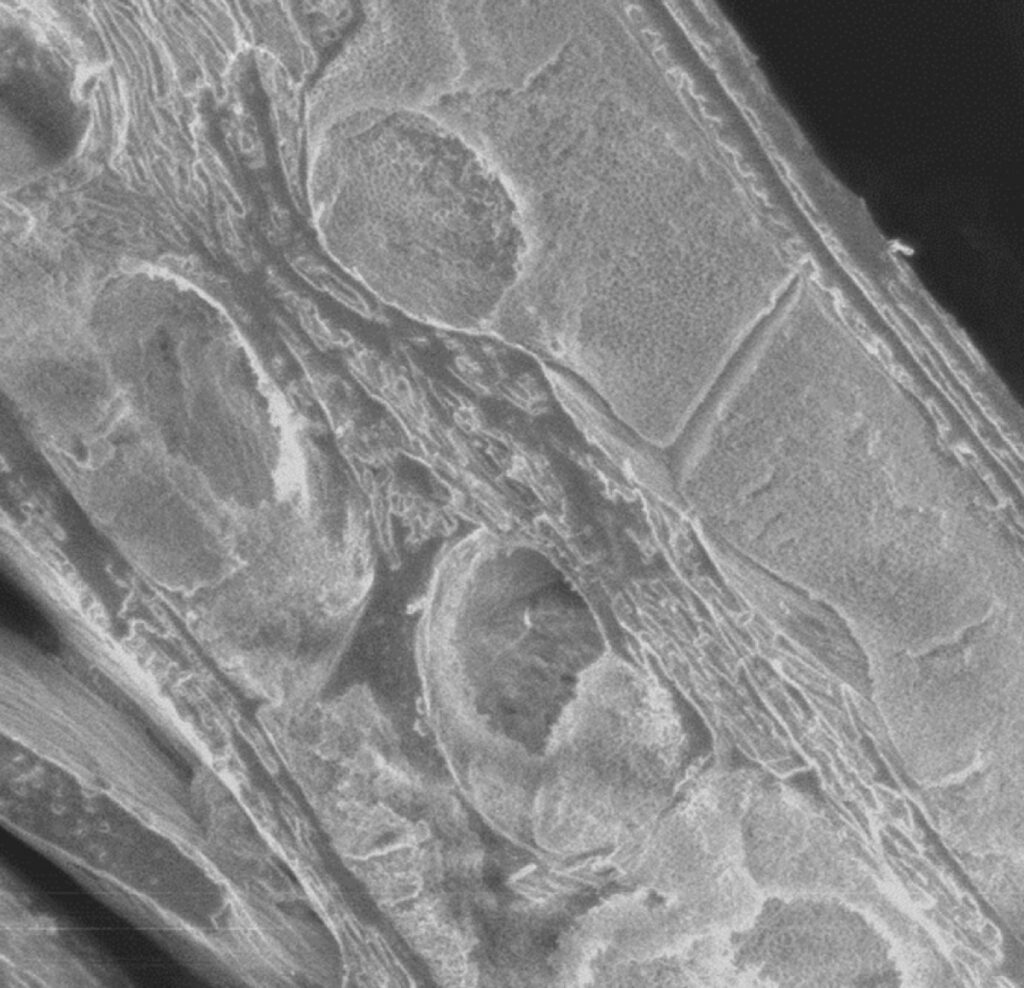

A scanning electron microscopy image of Kingfisher feathers reveals the semi-ordered nanostructure

Maria Kokkori/Northwestern University

Maria Kokkori/Northwestern University

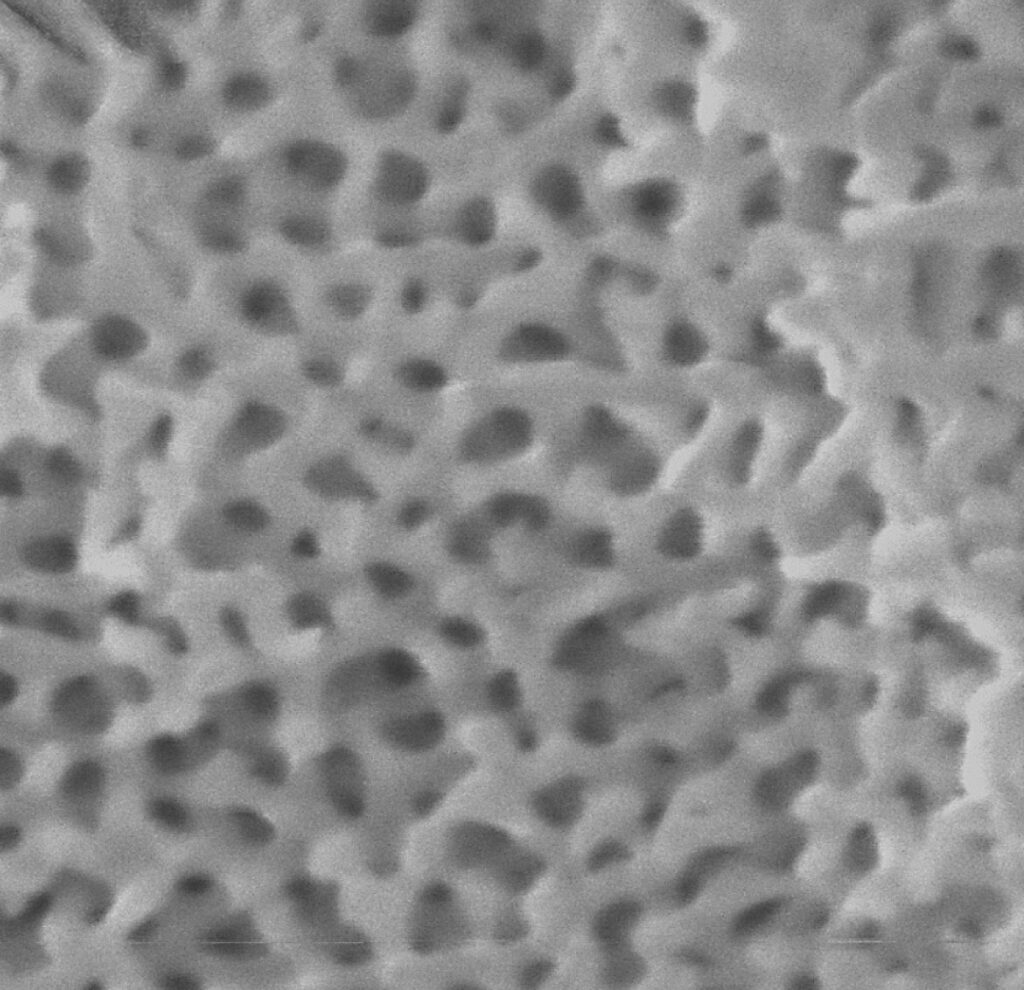

By increasing the magnification of the scanning electron microscopy image, researchers discovered a nanoscale, spongey architecture.

Maria Kokkori/Northwestern University

A scanning electron microscopy image of Kingfisher feathers reveals the semi-ordered nanostructure

Maria Kokkori/Northwestern University

By increasing the magnification of the scanning electron microscopy image, researchers discovered a nanoscale, spongey architecture.

Maria Kokkori/Northwestern University

The Northwestern team started looking at kingfisher feathers in tian-tsui objects via postdoc Madeline Meier, who has a background in chemistry and nanostructures and was interested in combining that expertise with studies of cultural heritage. The first step was to identify the bird species whose feathers were used in Qing dynasty screens and panels, as well as other materials used. Researchers carefully scraped away the topmost layers and imaged the feathers with scanning electron microscopy to get a better look at the underlying nanostructure. Hyperspectral imaging revealed how different areas of the screens absorbed and reflected light.

The team also made use of the center’s partnership with Chicago’s Field Museum, comparing the screen feathers with the museum’s vast collection of taxidermied bird species. The screens and panels contained feathers from common kingfishers and black-capped kingfishers, as well as mallard ducks (used to add green hues). Finally, X-ray fluorescence and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy enabled them to create a map of the various chemicals used in the gilding, pigments, glues, and other materials.

Most recently, the lab has partnered with Argonne National Laboratory and used synchrotron radiation to get an ever-better look at the nanostructure of kingfisher feathers. Synchrotron radiation differs from conventional X-rays in that it’s a thin beam of very high-intensity X-rays generated within a particle accelerator. Electrons are fired into a linear accelerator (linac), get a speed boost in a small synchrotron, and are injected into a storage ring, where they zoom along at near-light speed. A series of magnets bends and focuses the electrons, and in the process, they give off X-rays, which can then be focused down beam lines.

That makes it ideal for noninvasive imaging, since, in general, the shorter the wavelength used (and the higher the light’s energy), the finer the details one can image and/or analyze. It has become a popular technique for imaging fragile archaeological artifacts without damaging them—like Qing dynasty headdresses with inlays of kingfisher feathers. In this case, the imaging revealed that the feathers’ microscopic ridges have an underlying semi-ordered, porous, sponge-like shape that reflect and scatter light, thereby giving the feathers their gloriously brilliant hues.

“Long admired in Chinese poetry and art, kingfisher feathers have amazing optical properties,” co-author Maria Kokkori said. “Our discoveries not only enhance our understanding of historical materials but also reshape how we think about artistic and scientific innovation, and the future of sustainable materials.”

Source link